Improvising Out of Algorithmic Isolation

Becoming ungovernable means becoming illegible.

These miraculous machines!

Do we shape them

Or do they shape us?

Or reshape us from our decent, far designs?But we are learning.

We are learning to build for the future

From the ground up.

On how our co-evolution with machine intelligence transforms the fixed, self-authoring individual identity of the industrial era to the fluid, relational and dividual identity of planetary culture and consequent shift in subjectivity to that which defies measure, from which mind becomes an object for art and sacralization. In other words, rebelling against surveillance hypercapitalism means a hermetic retreat into the ineffable ground of Being.

I’m a lifelong committed improviser (in music, art, public speaking, and vocation) so this is something like a manifesto for the Taoist practice of “feeling our way across the river stone by stone” — with asterisks on “our”, “the river”, and “stone”, noting that even these seemingly-stable objects are themselves coarse-grained abstractions of stable “environmental” features co-enacted by…WHAT, exactly?

Originally written in 2021 for a compilation by Bennington College that stalled before printing, then published on Medium, and soon to be reprinted in my first book, How To Live In The Future (Revelore Press, 2025). For more in this vein, check out my lightning talk “AI-Assisted Transformations of Consciousness”, short essay “Refactoring ‘Autonomy’ and ‘Freedom’ for The Age of Large Language Models”, and Humans On The Loop Episode 01 — Reclaiming Attention from The Ravenous Maw of The Screen with Richard Doyle.

As usual, an extensive bibliography below for readers who want to go deeper.

Abstract (Take 1)

Evolution is improvisation. Innovation is the same appropriation of existing parts and recognition of affordances. Design is on a different timescale than biology (so far) but otherwise obeys the same dynamics. Algorithms, then, are acting inferences of the world, encoded expectations based on histories of interaction. None are final or complete. Externalities are unavoidable. This is a blessing and a curse: we cannot be reduced to n-dimensional descriptions, always offering surprise; but we can’t comprehend even the simplest thing in its entirety. This always-more-ness is an invitation for an insurrection, gives an opportunity to slip between the cracks of insufficient models. The gaps that trouble justice, the lacunae opened in the interstices in between known knowns, is where the underserved and marginal abide, and sometimes that’s a tragedy because the census doesn’t recognize their need — but sometimes it’s a chance to sneak up on a sleeping predator. An algorithm is a recipe is a hypothesis and we as artists get to offer up anomalies that prove them wrong. Our own improvisations are an algorithmic process but may work at scales or on axes unobserved by other algorithms: facial recognition algorithms can be jammed with stickers brandishing an adversarial design; the same game’s played by zebra stripes on lion eyes, and probably is why so many organisms cooked up psychedelic compounds in the first place, as a form of sabotage. Escaping the panopticon requires meeting its improvisation with our own. (Of course, we are merely differentiable and not extricable from The Machine, and then on second pass not even differentiable, so we need different measures by which to evaluate what constitutes “escape.”)

Abstract (Take 2)

In this essay, I explore algorithms as a form of improvisation. As artists, our improvisation with the dehumanizing algorithms of predatory surveillance capitalism is a kind of tango — an exploratory, open-ended, provisional, context-dependent, time-bound, blindspot-defined process of mutual adaptation. The economy — and the ecology of which it is a subset of dynamic interwoven agencies — is an evolutionary system, and evolution is improvisation via the appropriation of existing forms. The algorithms we design are just the visible tip of the algorithms we enact unwittingly, the action of distributed intelligence in a long, complex arms race with itself. The only way to win is to refuse the rules and act from true and nameless spontaneity.

Improvising Out Of Algorithmic Isolation

“Chaotic fecundity…propels every genuinely inventive cultural practice. All artistic activity, [Julia Kristeva] says, transpires ‘on the fragile border…where identities do not exist or only barely so’.”

– Eric White, “The Erotics of Becoming: Xenogenesis and ‘The Thing’” in Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 20, №3 (November, 1993) (1)“I change shape just to hide in this space cuz I’m still, I’m still an animal…”

– Miike Snow, “Animal”

There are many reasons to hold in suspect the attempt to quantify the world, but perhaps the best is that we only count what we perceive. Programmers know this (“garbage in, garbage out”); even a “perfect” algorithm trained on faulty data sets will misbehave. When we do not adhere to the precautionary principle, when we don’t test these systems in a kiddie pool where they can’t hurt someone, tragic consequences multiply. The blind spots of the people who decide how fine to slice the world, and the nth-order unexpected downstream outcomes that emerge from interactions happening beneath the threshold of a system’s sensitivity, seem as though they will define this century — and in those cracks fall living, feeling beings, not just people but non-humans on which we rely, or one day might.

This is not new. Mark Buchanan, in a 2018 Nature Physics editorial (2), draws on copious evidence from many disciplines to argue that there is a bias for simplicity in science and in nature: it takes calories, after all, to think, and all adaptive systems are innately “lazy”, seeking rest. Science cleaves to the aesthetics of the elegant because parsimony is what brains and nature have in common: friction-minimizing, energy-diffusing, and uncertainty-reducing networks. Generally speaking, things do not fall up. In order to perform, an inferential organ must obey this, and becomes a microcosm of the world it models…and because no 1:1 map of everything is possible, important details blur and all prediction’s fallible.

This is evident in economics, a field of study that has slowly been transformed by insights from the evolutionary sciences (3). Every actor in a market is anticipating everybody else’s actions, running simulations of the other parties. As soon as someone changes their behavior based on an updated model, this informs and alters every other model held in every other mind, eventually obsoleting even the most complete and accurate “theory of everything.” None of us can predict ourselves forever perfectly, much less each other. Surprise rules everything nonlinear, and so as humankind depends increasingly on outboard algorithmic systems to throw switches and determine outcomes in society, we can all expect more twists of fate.

But let’s back up, because while algorithms cannot render flawless models of a world and its inhabitants — while AI architects cannot obtain omniscience or even know for sure how many axes offer truly optimal if partial answers — their creations still contribute to the co-determination of a biospheric arms race in least-effort educated guesswork. Complex systems scientists Jessica Flack and Melanie Mitchell write at Aeon Magazine (4) about how test grades often offer useless metrics once the students learn how they are being graded; and in fact this undermines the work of education insofar as it distracts them from the point of education, which is a practical, transferable grasp of the subject. But this is not an easy thing to fix, because the teacher does not have infinite time and energy to test students in all real-world applications of the knowledge that they’re hoping to impart…and so exams are low-dimensional encodings of real understanding, loose sieves and not true measures of a person’s comprehension. The same is true for key performance indicators in the workplace, which is why employees “rise to the level of their incompetence.” Past victories do not prepare a person or a piece of code for anything outside their worldview, which is as narrow as it can be and get by, and is reinforced in laziness by its successes. Ultimately, something has to give.

This is why the fear of algorithms taking over has two sides, and only one is valid. Machine intelligence, while in some ways faster or more comprehensive in its information processing, is no less the product of the selfsame evolutionary forces that produced the human mind. It is as partial as we are — and arguably more so, as humanity has had 500 million years to tune its powers of analogy, whereas computers, merely decades old, cannot learn from experience to form illuminating metaphors and act appropriately under novel circumstances. But even on the day that they learn how, the differing histories of machine and human being, and the differing bodies, will guarantee that each side will remain opaque to one another in important ways. The fear of being known completely by machines is not the problem.

The problem with AI, as the problem is with other people, is being misunderstood. Models of dynamic human interaction made by Vicky Yang, Tamara van der Does, and Henrik Olsson (5) show how in-group/out-group factions form, and why so many people find themselves caught in the cross-fire, aliens to both sides. So it is with any software sorting engine: someone, always, is invisible to code, and the less diverse the coding team the more will be invisible. But this sword has two edges.

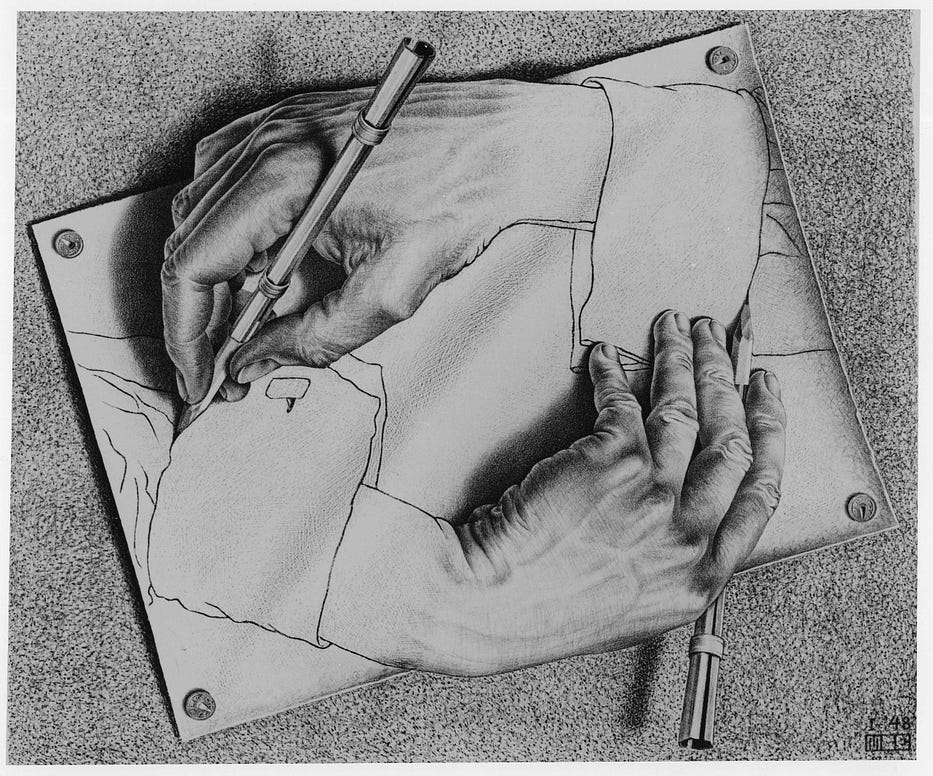

Software algorithms are perhaps one kind of cell in the much larger bodies orchestrated by financial-profit-driven business models that pump externalities out to anyone and anything that can’t hit back (at least in ways that matter to the system’s information aggregation and reward anatomy). A corporation’s board can only care about the quarterly returns, until — through shifts in popular opinion or through a transformative new form of measurement — less imminent and more abstract realities come into focus. We are all individually guilty of this short-term bias due to metabolic limits and imposed societal constraints on our attention, which is why long-term issues such as climate change pose such immense collective action problems. It takes a new incentive to exert the energy to grow new senses, which is why the eye appears all of a sudden in the fossil record, simultaneously in several independent lineages. Something similar is happening now with three-plus-bottom-line reporting (6): even noble efforts to map everything to save it add in some way to the ouroboros of the market eating its own tail. The race is never over, and each twist ratchets up the cost of all this sensitivity and navigation, and produces novel mysteries…more opportunities to find, and miss. Because the arms race overturns its own rules ever-faster all the time, four hundred years of modern technological development will consummate in a return to wilderness: a world in which we have replaced the predators that stalked us in the Pleistocene with monsters of our own creation, and remain as imbricated as we ever were in an ecology we cannot understand and cannot stop from harming us.

The upside is, just as with bears and tigers, algorithms are a different kind of smart than we are. To the degree that we’re misunderstood, we can surprise them. Or become and stay irrelevant, or undesirable. In terms of an analogy, we seal our food in airtight camping ware and wear a wide-eyed mask behind our heads while in the woods, so we are always “watching” anyone who tries to watch us. (That’s the Argus: all one hundred eyes around a globe head, half-shut/half-asleep and losing sheep, a blind spot unavoidable. This depth of strangeness even in familiar objects, this never-known, is worth remembering when worrying about the possibility of being fully grasped by the surveillance monster. There is always a horizon, any way you travel.)

What will not help is ever-finer resolution of identity, for it’s the granular distinctions by which Westerners have been enculturated since at least the 1970s, when lifestyle marketing arose to generate the hypermodern, hyper-tailored, long tail frictionless consumer (7, 8). It isn’t by retreating into smaller boxes that we save dignity or culture from Accelerationism’s all-commodifying maw; that’s just helping it chew you before it swallows, choosing to be cornered for the sheer convenience of the scaffolded identities you’re sold (and their admitted concomitant social perks) (9).

As with neighborhood food security, the far more challenging but antifragile play is “Grow Your Own,” which means acknowledging the nameless source of being prior to our concepts of ourselves, and anchoring in that. It means allowing the ideas of self to come and go and models to reweave and weave, and watching one’s own algorithms trying to keep hold. Improvising out of algorithmic isolation may one day mean, for some people, pushing past the relatively stable forms of our embodiment on evolutionary timescales, into shapes that moderns wouldn’t recognize as human. Then again, as Zygmunt Bauman argues, modernity has always had a dual fixation with control and order on one hand, and on the other, radical self-undermining change (10).

For now, this kind of flux is just a symbol beckoning us into an unscripted dance: with our machines and with each other until, as Rachel Armstrong puts it, “any sufficiently advanced civilization is indistinguishable from nature” (11). Not knowing what to look for when we search for sentience in outer space, one possibility is that our neighbors got too good at improvising as a form of crypsis: physicists demonstrated back in 1999 that optimal encoding of a message makes it impossible to differentiate from noise by anyone but the intended listener (12), and similarly, Edward Snowden once suggested that encryption could be blinding us to night skies full of lively ET correspondence (13).

Ultimately, algorithms of all kinds — instantiated in computers, or incarnate in behavior and anatomy of living organisms — are imprecise and improvised, contingent on their shifting fits within an ever-changing world: “All models are wrong, but some are useful,” at least for a time (14). Escaping from the jaws of the panopticon means challenging not just the expectations of machines, but of our own mechanical conditioning. There is no fundamental difference: the systems we’ve devised to cage each other are extensions of the uncertainty-reducing flesh automata (15) by which we name and thus preclude ourselves, indulge in the jouissance of self-destructive habits (16), and render lazy maps with which we paper over inconvenient facts (17). As always, but perhaps especially in our warming world, cold equations don’t suffice in an encounter with what Nora Bateson calls “warm data” (18, 19, 20). The way out takes us past intention and desire, identity and understanding, through surrender to a mystery that nobody — no brains of carbon or of silicon — can solve.

“You must always remember: we can predict many things, but never the actions of human beings.”

— Zygmunt Bauman (21)

Bibliography

(1) The Erotics of Becoming: Xenogenesis and ‘The Thing’” by Eric White for Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 20, №3 (November, 1993)

(2) A natural bias for simplicity by Mark Buchanan for Nature Physics

(3) Complexity Podcast Episode 13: W. Brian Arthur on The History of Complexity Economics by The Santa Fe Institute with Michael Garfield (host/producer)

(4) Complex Systems Science Allows Us To See New Paths Forward by Jessica Flack and Melanie Mitchell for Aeon

(5) Falling Through the Cracks: A Dynamical Model for the Formation of In-Groups and Out-Groups by Vicky Chuqiao Yang, Tamara van der Does, and Henrik Olsson on arXiV

(6) MetaIntegral.com by Sean Esbjörn-Hargens

(7) The Century of the Self by Adam Curtis

(8) On Hypermodernity by John David Ebert

(9) Rune Soup Podcast: Accelerationism, Meaning, and Exit by Gordon White & James Ellis

(10) Liquid Modernity by Zygmunt Bauman

(11) Any Sufficiently Advanced Civilization is Indistinguishable from Nature by Rachel Armstrong for IEET

(12) The physical limits of communication or Why any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from noise by Michael Lachmann, M.E.J. Newman, Cris Moore in The American Journal of Physics

(13) Edward Snowden: we may never spot aliens thanks to encryption by James Vincent for The Guardian

(14) “All models are wrong” (Wikipedia) attributed to George Box

(15) (Selected papers on the free-energy principle and the brain)by Karl Friston et al.

(16) What’s Expected of Us in a Block Universe: Intuition, Habit, & ‘Free Will’ by Eric Wargo

(17) Complexity Podcast Episode 34: Better Scientific Modeling for Ecological & Social Justice by The Santa Fe Institute with Michael Garfield (host/producer)

(18) The Cold Equations by Tom Godwin for Astounding Science Fiction

(19) Cold Equations and Moral Hazard by Cory Doctorow for Locus Magazine

(20) Nora Bateson on Warm Data vs. The Cold Equations by Michael Garfield on Future Fossils Podcast

(21) A conversation with Zygmunt Bauman by Hannah Macaulay for The Gryphon