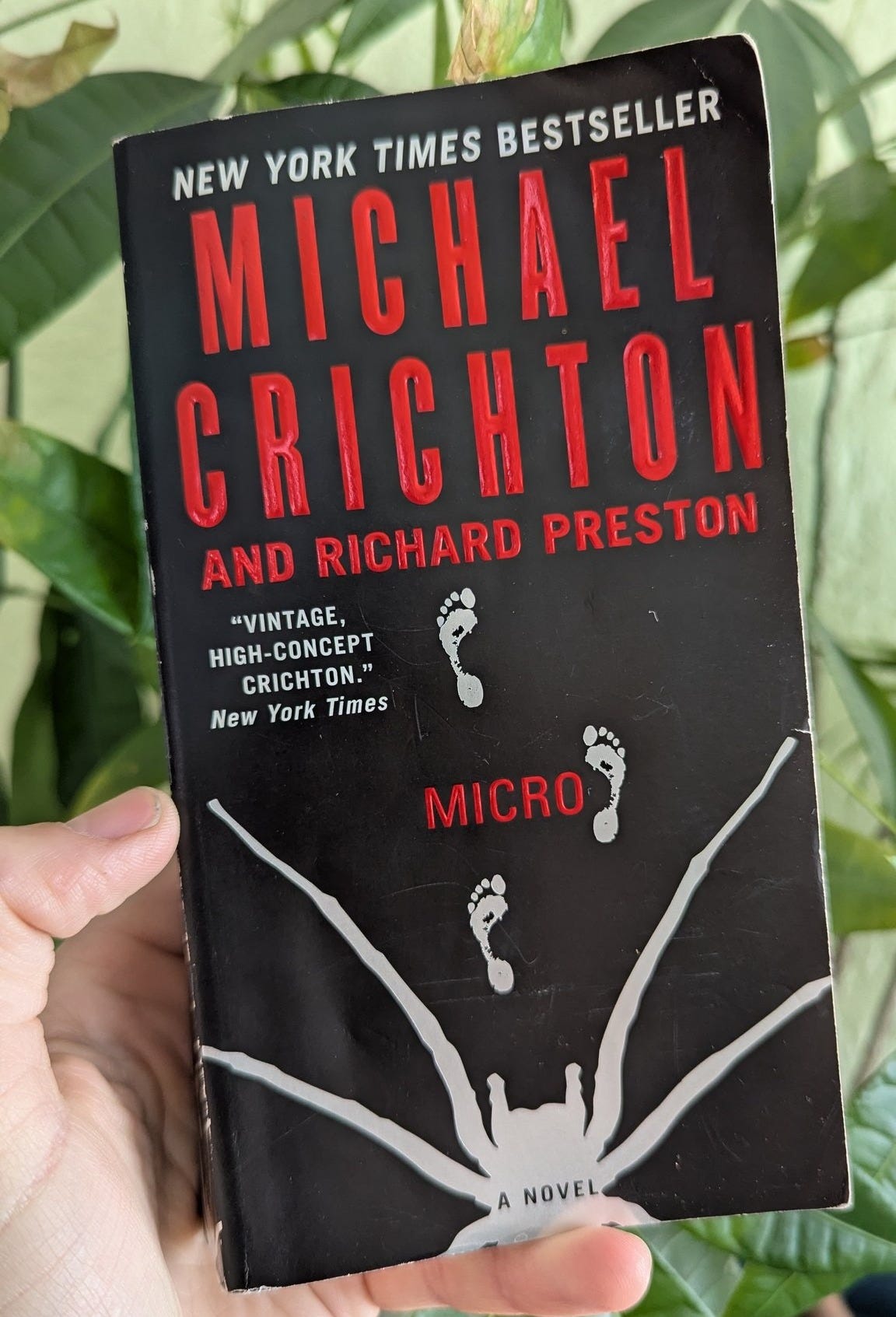

🕷️ Terror & Wonder Above & Below: Michael Crichton & Richard Preston's Micro

A book that says the loud part quiet and the quiet part loud. But maybe it's an artifact of scaling...

I just read Micro while laid out with a fever. The timing was perfect for meditating on the horrors of the very small...nothing like having one’s body hijacked by invisible replicators to prime you for thinking about how to human-scale mesocosm depends entirely on forces both bigger and smaller than we are evolutionarily prepared to observe or address.

Crichton fans seem to mostly hate this book, I imagine mostly because they're mad that he's dead. Critics panned it for being a familiar premise, reminiscent of Fantastic Voyage and Honey, I Shrunk The Kids, but it seems like nobody remembers that even Jurassic Park was published years after the relatively obscure kids' book series Lost In Dinosaur World (a curiosity I noted in this piece for the benighted Jurassic Worlding) and that Crichton excelled mostly not in totally original ideas but in giving wondrous topics a thick glaze of verisimilitude to substantiate his two consistent deliverables: 1) visceral terror and 2) a platform for warning us about the evils of privatized research beyond the scope of public oversight and scrutiny. The persistent psychogeographic overlay of “Honey, I Shrunk The Grad Students” actually works in its favor because this book preys on your priors. (Befriending an ant? Nope!) Sci-fi thrives on Chiang’s Law: it’s a genre about “strange rules” and there are few stranger rules than “physics works totally differently when you’re the size of a fingernail” (more on that below).

I had to laugh at the reviewers who didn't like the main characters, seven hyper-competitive Cambridge, Mass grad students thrust into the micro-world as unwitting bystanders of corporate espionage. Have they ever met Ivy League grad students? The jungle of academia, with its “publish or perish” selection algorithm, its labor-harvesting parasitoid advisors, it’s catch-as-catch-can grant application metabolism, and its woefully uneven distribution of reward via citation bias — let’s not even talk about the “kids of Ivy League parents” croneyism — seems like the perfect training ground for students thrust into the red-in-tooth-and-claw micro world of the Honolulu rain forest.

Accusations of thin character development in a techno-thriller fell flat for me; these are people who only managed a fighting chance against monstrous insects, arachnids, birds, and bats because of their deep disciplinary knowledge of molecular biology and animal behavior, and watching them turn their book- and lab-smarts into practical know-how in a life-or-death situation, petty academic rivalries fading into foxhole camaraderie, was the most satisfying and informative meat of the whole read. Although this book is thin on Ian-Malcolm-esque theoretical diatribes — Preston focuses on action, and delivers with some of the most unnerving threats I’ve ever read — it’s easy to imagine the planned Crichton manuscript running thick with complex systems lectures on how multi-agent coordination is the engine for emergent meta-individuality and major evolutionary transitions. Despite the swiftly escalating headcount and low survivorship, this is nonetheless a story about the success of sociality, an ode to doubling down on teamwork under pressure (which is, incidentally, precisely where science on the whole finds itself under the current hostile conditions of the United States government tech coup — see my response to C. Brandon Ogbunu’s latest piece at Undark here).