🌎 The Underview Effect

On the messy, divisive politics of our emergent planetary culture.

This is the first part of a two-part article on 1) why space tourism isn’t working as advertised and 2) what it will actually take for humankind to develop a planetary perspective. It’s more “screed” than “carefully fashioned essay” so if you want one of those, go check out my debut feature at Aeon Magazine for something even crazier and more audacious. I’m trying to get podcasts back on a regular schedule, but I’m also sitting on half a dozen other unfinished essays, helping boot up a new society for sane AI discourse and a new tech-enabled services consultancy, and being a present father and husband. So thank you for your patience!

Subscribe for Part Two soon, plus a ton of excellent upcoming podcast guests:

And become a member for every unreleased episode, plus new ones as soon as they’re recorded, and to join in on our wonderful monthly hangouts.

Why This, Why Now?

It’s time to offer what I hope is a usefully bigger frame for the controversial all-female Blue Origin spaceflight. I know talking about NS31 might seem a bit stale as far as the news cycle is concerned, but:

Inequality is a generation-defining hot topic right now and if quantitative historian Peter Turchin is right (and every indication suggests he is), it will remain so for years to come. Read “The Double Helix of Inequality and Well-Being” later for some useful framing. I also strongly recommend Michael Flynn’s “An Introduction to Cliology”, the afterword to his 1990 novel In The Country of the Blind, which was my introduction to the discipline of quantitative history and utterly blew my mind when I first read it.

William Irwin Thompson claims the process of planetization started in 1945 and has at least a century-long arc. The promise and ethical complexities of space tourism are developing stories and we have a very long way to go. Whether or not you grew up thinking you’d be kicking it in space by now, whether or not you even want an extraplanetary future, who goes into space and why will be the center of debate for years to come.

But let’s start where we are, in the superposition of what is and what could be: looking up from the only planet we have ever known, while also looking down from orbit.

To Arrive Where We Started

This piece was inspired by three perspectives on the issue from members of the “space community” — professional believers that space is “for all humankind” (see also the marvelous Tanya Harrison in Future Fossils 138) — smart and thoughtful people with a very long horizon. As grist for thinking out loud about the benefits of space tourism, Exhibit A is astrobiologist Graham Lau’s comment on Facebook (emphases mine):

I get that some people are angry about NS31 and the women who just went to space through Blue Origin. Lots of people want to make fun of it, and some have taken to commentary and jokes about the women who were on the mission.

For instance, I've seen these pics going around suggesting some absurdity for Katy Perry to kiss the ground after her adventure. The pics appear to be suggesting that the short duration of the flight means that maybe she had no place doing that. As though an experience is less valuable because it is short lived.

Sure, there are issues with the current realm of space tourism and human space exploration, especially as it's become associated with the wealth of the billionaires funding these private missions. But we don't really need gatekeepers to tell people how they should experience awe and wonder—even if the people having the experience are celebrities or their experiences were fleeting.

If anything, I'd hope of all of you who've shared such jokes to have a chance to have such an experience yourself.

Revel in a sunset, see your own child being born, climb a mountain, read a book that makes you cry, get the chance to say goodbye to a loved one on their death bed, dance like no one is watching. All of these things can be experienced in awe and wonder—even if others might want to make fun of you for how you experience it.

The point here — that wonder is an unalloyed good — is itself up for debate. Years ago I watched a conversation between Erik Davis, a personal hero and inspiration, and “Shots of Awe” influencer Jason Silva in which Jason confessed he couldn’t actually feel the awe he proselytizes on YouTube by just sitting under a tree. He needs to be overwhelmed by the technological sublime — jet engines, IMAX theaters, speculation on the defeat of death with bio-engineering and brain uploading — and can’t get it, to borrow from psychedelic philosopher Terence McKenna, “on the natch”. Jason’s version of “experiencing awe in nature” is going for a walk in the park with a necromantic generative AI simulacrum of McKenna and sharing it on TikTok. Can it get any more ironic than having a “conversation” with a language model on a live stream about dis-intermediating direct experience by dropping the linguistic overlay?

A truly “planetary” view doesn’t strictly require us to see the planet from space to “get it”. Understanding our embeddedness in ecological context, our fragility and unity, starts in the context. And the joke is on you if it takes getting thousands of miles away to realize you have never really left. But then of course, there’s the story of Siddhartha Gautama, who left his wife and child to seek enlightenment and on attaining it returned to his justifiably angry spouse. “Did you really have to leave to find your awakening?” “Well…no.” Awakening is available everywhere. But he did, and it is what it is. Maybe there are less expensive ways of finding our way home, but then again the more deeply embedded you are in the big machine, the more work it takes to extract yourself and see you have to de- and re-territorialize yourself.

Famous travel writer Rolf Potts changed my life with his book Vagabonding: The Uncommon Art of Long-Term World Travel, in which he spends the last chapter on what might be the real point of “getting out”: coming home and seeing everything you took for granted, and encountering it all as if an alien within your native culture and environment. This transformation is a core trope in the hero’s journey and appears in one of the most common refrains in space science discourse:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

— T.S. Eliot, from “Little Gidding,” Four Quartets (1943)

But it’s harder to justify space tourism if we don’t literalize exploration as a voyage over geographic distance. Near-death experiences, psychedelics, and other interruptions to the linguistic overlay of familiarity consistently reveal a holographic world in which these revelations are abundantly on offer anywhere in space, and travel is what happens in the mind.

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

— William Blake, “Auguries of Innocence,” Lines 1–4 (1803)

Holding Eliot and Blake together, we might find better ways to engineer “the Overview Effect” with fewer externalities. Where can we look for inspiration?

Part of the problem here is in the concept of “space tourism” itself. It’s one thing to get your passport stamped and come home with a photo roll of castle selfies, and another far more rare and precious thing to let the journey do its work on you. You can spend your life in trains or planes, in hostels or resorts, without ever truly interacting with the otherness of foreign cultures and ecosystems. Only in unguarded personal encounters with the unfamiliar, making space for other ways of being, are we transformed. Biologist David Krakauer captures the difference between transformative travel and tourism in a more fundamental statement about the evolution of intelligence—as a tension between adaptation and niche construction—when he says, “You can make yourself smarter or you can make your environment dumber.” Going into space with the intent to bring home an experience, however wondrous, is on the order of transforming Places People Live (Helsinki, Venice, Barcelona, Santa Fe) into subservient tourist economies: a settler strategy, lifestyle consumerism that makes few real demands on travelers who carry their convenience on their backs but exports adaptive pressure to weird, rich, mysterious locales until they flatten into “destinations”. (I grew up in Orlando; Ask Me Anything.)

Which means that even if we accept Lau’s original argument on its face — that wonder is wonder and who are we to judge — there are other, more compelling critiques of NS31. One of them comes from complex systems science and can be abbreviated into something like, “Is blowing certain people’s minds enough to make things better for the rest of us?”

On Faith in Scalar Interventions

What will it take to get a planetary “us” and see civilian astronauts as a victory of humankind? Some people see global cultural change as something they can engineer—not an unpredictable emergent property of non-computable complex multiscale dynamics but an instrumental goal to be effected by changing the minds of influential people. “If only [person in the news each day] would [have the experience that changed me]” is a very common trope. (Exhibit A: delight in the fanciful fake Trump memoir Born Again: How LSD Changed My Life.)

I’m deeply skeptical of this. The revolutionary movements of the 1960s dreamed of turning people on with psychedelics or pictures of the Earth from space, but they saturate the world we live in now and humankind is even closer to the brink.

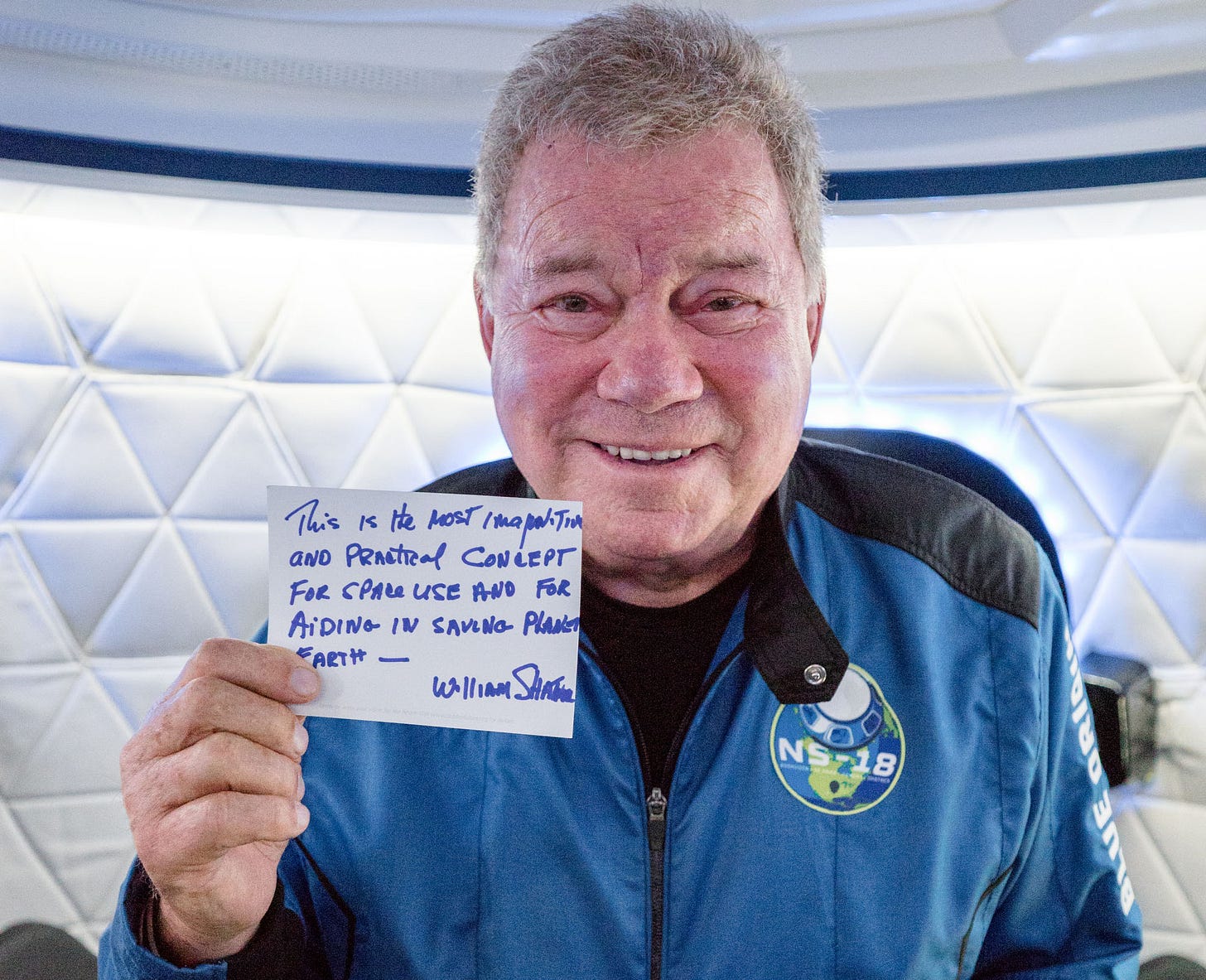

William Shatner fell to his knees and kissed the Earth after his landing:

Now it’s January 2026, popular protests against despotic leadership are erupting everywhere, and the post-war framework of international collaboration is falling to pieces. Meanwhile, Trump looks to Greenland and Musk looks to Mars like the Great Houses of Herbert’s Dune look to Arrakis:

For the last time:

Turning up the noise in people’s brains does not produce reliable shifts in their values, if any (see Pace and Devenot’s “Right-Wing Psychedelia: Case Studies in Cultural Plasticity and Political Pluripotency” for a sobering look at this). And do I even need to tell you that nearly every household name in Big Tech uses psychedelics to better serve the twin opposed goals of Industrial Modernity, disruptive innovation and control?

But I want to be generous, because I used to believe this kind of thing. So let’s start with comments from former Executive Director of Space for Humanity Rachel Lyons, which we can boil down to “The cost of sending people into space is an investment into the impact they’ll make when they return transformed as cosmic citizens”:

Astronauts consistently report coming back from space with a whole new perspective.

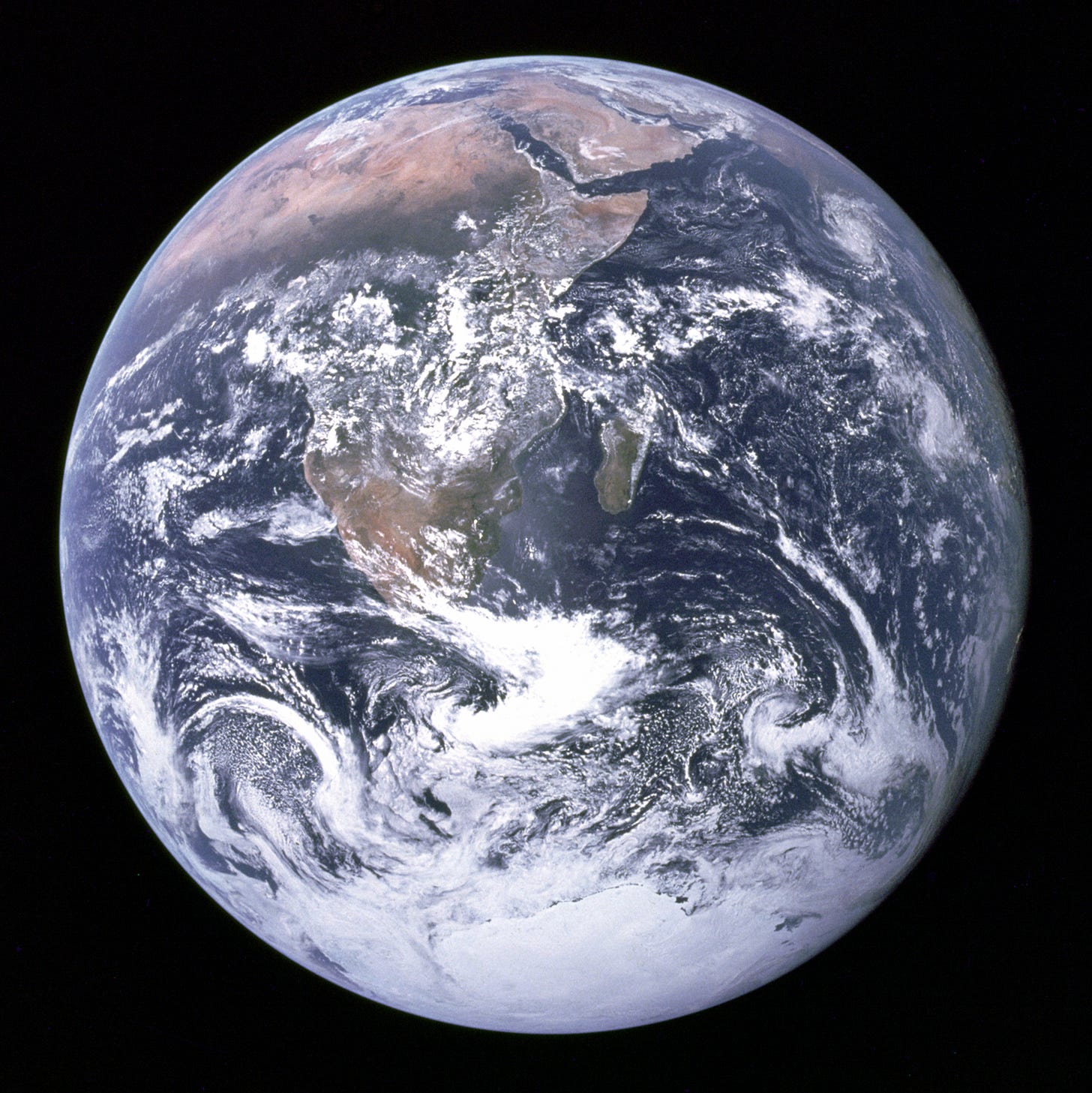

They see Earth shining, suspended in the void…

A fragile blue marble with a paper-thin atmosphere…

One planet. No borders. Interconnected with all of life.

They change.

Since Yuri Gagarin first went to space in 1961, astronauts have returned with new awareness about the environment, humanitarian issues, politics—even their role in their local communities.

If you watched the livestream (blueorigin.com/live), you saw it: the emotion in these women’s faces when they landed.

They were deeply moved. Every one of them said it was one of the most meaningful experiences of their lives.“Katy Perry?? Come on.”

As my friend Daniel Fox said, I think who ever chose her deserves a serious raise.

Her songs are inspiring millions. When so much music today promotes violence, unhealthy sex, and escapism (and permeates the collective unconscious!!!), her work uplifts.

After landing, she said this flight made her fall in love with humanity.

She committed to writing music about the experience.

Do you understand what that means? One of the most followed artists on the planet is about to release music about the Overview Effect.

That’s billions of people… receiving the awe, unity, and reverence for people and our planet—through art.

To me, that’s worth so much more than the cost of a seat.

Is taking Katy Perry into space an investment in the future inspiration of millions of people? Maybe. But what looks like the whole-cloth creation of value from one angle looks like extraction of another.

I’m reminded of William Irwin Thompson’s comments on the Irish Revolution of 1916, how W.B. Yeats was criticized for being a poet instead of firing bullets on the front line, but did more than anyone to foster the identity of the Irish people that made that revolution thinkable. Clearly, as Steve Bannon (ha) has noted, “culture is upstream of politics”…and yet, the ROI on gestures like Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth movement isn’t easy to measure, predict, or ensure.

The historic first photos of our entire planet in one frame inspired a sense of mystical participation and ecological activism in some, and in others it amped up technocratic colonialist ambitions by deluded them into thinking they could actually comprehend planet-scale systems. (It should go without saying that The Overview Effect wasn’t enough to radically alter Jeff Bezos. Even if it had, would his board have let him tank their profits? Edgar Mitchell’s spaceflight revelations compelled him to found The Institute of Noetic Sciences, but didn’t alter the course of the military industrial complex one iota.)

For a superb treatment of these problems, see Chapters 7 through 11 of Joshua DiCaglio’s book Scale Theory: A Nondisciplinary Inquiry, which I think everyone who cares about these questions ought to read. DiCaglio argues more cogently than anyone how individual transformation doesn’t clearly map onto cultural formation of a cosmic identity, and we don’t know how to effect these kinds of scalar interventions. Trying to engineer them by “turning on” celebrities and HNWIs is a catastrophic failure of complex systems understanding akin to the logical fallacy of Trickle Down Economics.

Yeats’ poetry did the trick because it spoke to common experience, gave voice to something the Irish knew firsthand. It sacralized the familiar. If you weren’t already Irish, it didn’t make you Irish. If I write a song about my awesome marriage, and you have an awesome marriage, you and your partner might adopt it as your own. If you’re single and unhappy, I probably just seem like I am gloating. If you could buy your way into an awesome marriage, you might be inspired to make the effort…and if I have the means, I might market that to you the way some people fall in love with some quaint seaside town and then decide to buy it up for short-term rentals.

But human beings love vicarious experience, even when it doesn’t truly scratch the itch. Unboxing videos are very popular because consumers love the thrill of novelty—but they ultimately persist as a genre because they sell the goods, not because they give you the first-person satisfaction of unboxing it yourself. Betting on the industrial machinery of pop music to induce Perry’s wonder in millions of people is like expecting porn to help you fall in love with you who are. I think (and this is evident from how most people actually reacted at the time of NS31) a handful of lucky space influencers are more likely to pour salt in the wound of our deeply stratified society than heal that wound.

Or people think they’ve been to space and get it when they don’t. Just as Neil Postman argues in Technopoly that mechanical printing has drained the symbolic power of the image, the more we saturate pop culture with this kind of secondhand account, the more we satiate ourselves with empty reproductions. Almost sixty years after the first publication of the famous Blue Marble photo, it’s an 🌍 emoji we drop in chats without a second thought. Human minds habituate to novel stimuli with awesome speed. Even tripping can become “whatever” if you’re on drugs every day.

If the day ever comes that anyone can go to orbit any time they want, will that finally do the trick? Or will we just sleep through it, the same way we sleep through commercial jet travel today? See the cancelled Louis CK’s riff with Conan O’Brien on how “Everything’s amazing and nobody is happy”—or how Heywood Floyd snoozes through his trip to the Moon in 2001: A Space Odyssey:

I don’t want to reduce this to “people suck,” but it simply isn’t as easy to buck the default mode network and install a permanent new cosmopolitan identity as running a savvy marketing campaign. And even if you do have a transformative experience, you might come home proselytizing to people who decide you’re just crazy. It’s arguably better than turning turning The Final Frontier into Real Housewives of Low Earth Orbit, but Western civilization is at or near Peak Cynicism right now and earnest messages of unity just don’t hit like they used to. Especially when they’re propagated through the polarizing hypermodern engagement-farming media machine.

Futurama nailed this in a wonderful short clip:

So: The Overview Effect only works for some people, their influence isn’t guaranteed, things can backfire at any step of the process. In other words, with space as with other forms of mind expansion, set and setting matter. The Overview Effect won’t scale unless we are already at least on the cusp of planetary culture. When we watch somebody weep on landing, kiss the Earth, and rave about how identity politics are trivial in cosmic context, we need to feel like “they” are “us.” Like they are speaking for the planet we already know we are.

Meanwhile, no matter how many cells in the biospheric organism get The Overview Effect, this is what it looks like to everyone else:

If we can’t open borders on the ground, we definitely can’t open borders in the sky.

And if we can’t open the sky so everyone can feel what Perry, Shatner, and the rest of the chosen few are privileged to feel, it’s hard to argue for open borders on the ground.

We have a circular problem on a spherical playing field that begs for a hyper-spherical solution.

…So What Does It Take To Be Planetary?

I’ll offer my answer to this question in Part Two, coming soon.

In the meantime, some related listening from the last two years of dialogues: